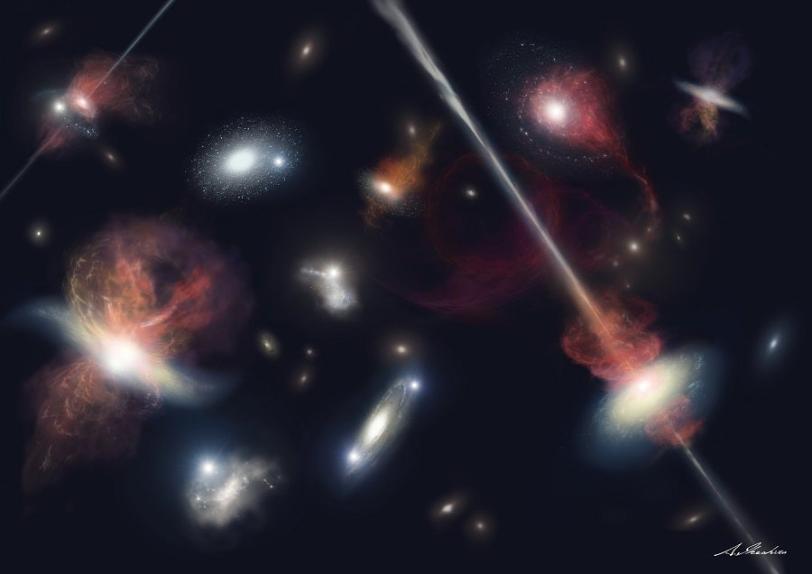

Cosmos Seeded with Heavy Elements During Violent Youth

Traces of iron spread smoothly throughout a massive galaxy cluster tell the 10 billion-year-old story of exploding supernovae and fierce outbursts from supermassive black holes sowing heavy elements throughout the early cosmos.

By Lori Ann White

New evidence of heavy elements spread evenly between the galaxies of the giant Perseus cluster supports the theory that the universe underwent a turbulent and violent youth more than 10 billion years ago. That explosive period was responsible for seeding the cosmos with the heavy elements central to life itself.

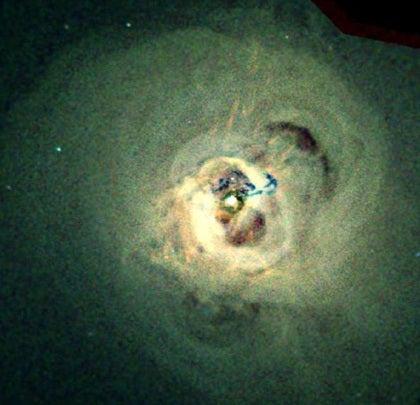

Researchers from the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC), jointly run by Stanford University and the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, shed light on this important era by analyzing 84 separate sets of X-ray telescope observations from the Japanese-US Suzaku satellite. Their results appear today in the journal Nature.

"We saw that iron is spread out between the galaxies remarkably smoothly," said Norbert Werner, lead author of the paper. "That means it had to be present in the intergalactic gas before the Perseus cluster formed."

The even distribution of these elements supports the idea that they were created at least 10 to 12 billion years ago. According to the paper, during this time of intense star formation, billions of exploding stars created vast quantities of heavy elements in the alchemical furnaces of their own destruction. This was also the epoch when black holes in the hearts of galaxies were at their most energetic.

"The combined energy of these cosmic phenomena must have been strong enough to expel most of the metals from the galaxies at early times, and to enrich and mix the intergalactic gas." said co-author and KIPAC graduate student Ondrej Urban.

To settle the question of whether the heavy elements created by supernovae remain mostly in their home galaxies or are spread out through intergalactic space, the researchers looked through the Perseus cluster in eight different directions. They focused on the hot, 10 million degree gas that fills the spaces between galaxies and found the spectroscopic signature of iron reaching all the way to the cluster's edges.

"We estimate there's about 50 billion solar masses of iron in the cluster," said former KIPAC member and co-author Aurora Simionescu, who is currently with the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency as an International Top Young Fellow. "We think most of the iron came from a single type of supernovae, called Type Ia supernovae."

In Type Ia supernovae the stars are destroyed and release all their material to the void. The researchers believe that at least 40 billion Type Ia supernovae must have exploded within a relatively short period on cosmological time scales in order to release that much iron and have the force to drive it out of the galaxies.

The results suggest that the Perseus cluster is probably not unique, and that iron – along with other heavy elements – is evenly spread throughout all massive galaxy clusters, said Steven Allen, a KIPAC professor and head of the research team.

"You are older than you think – or at least, some of the iron in your blood is older, formed in galaxies millions of lights years away and billions of years ago," Simionescu said.

The researchers are now looking for iron in other clusters and eagerly awaiting a mission capable of measuring the concentrations of elements in the hot gas with greater accuracy.

"With measurements like these, the Suzaku satellite is having a profound impact on our understanding of how the largest structures in our universe grow," Allen said. "We're really looking forward to what further data can tell us."

The research was supported by the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency and by the US Department of Energy.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.